| Marketing Education | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Lars Perner at the Marshall School of Business

|

|

Lars Perner, Ph.D.

|

My current research focuses on consumer behavior, non-profit fundraising, and "win-win" deals. I also maintain an interest in the autism spectrum.

Delivering customer value. The central idea behind marketing is the idea that a firm or other entity will create something of value to one or more customers who, in turn, are willing to pay enough (or contribute other forms of value) to make the venture worthwhile considering opportunity costs. Value can be created in a number of different ways. Some firms manufacture basic products (e.g., bricks) but provide relatively little value above that. Other firms make products whose tangible value is supplemented by services (e.g., a computer manufacturer provides a computer loaded with software and provides a warranty, technical support, and software updates). It is not necessary for a firm to physically handle a product to add value—e.g., online airline reservation systems add value by (1) compiling information about available flight connections and fares, (2) allowing the customer to buy a ticket, (3) forwarding billing information to the airline, and (4) forwarding reservation information to the customer. It should be noted that value must be examined from the point of view of the customer. Some customer segments value certain product attributes more than others. A very expensive product—relative to others in the category—may, in fact, represent great value to a particular customer segment because the benefits received are seen as even greater than the sacrifice made (usually in terms of money). Some segments have very unique and specific desires, and may value what—to some individuals—may seem a “lower quality” item—very highly.

Some forms of customer value. The marketing process involves ways that value can be created for the customer. Form utility involves the idea that the product is made available to the consumer in some form that is more useful than any commodities that are used to create it. A customer buys a chair, for example, rather than the wood and other components used to create the chair. Thus, the customer benefits from the specialization that allows the manufacturer to more efficiently create a chair than the customer could do himself or herself. Place utility refers to the idea that a product made available to the customer at a preferred location is worth more than one at the place of manufacture. It is much more convenient for the customer to be able to buy food items in a supermarket in his or her neighborhood than it is to pick up these from the farmer. Time utility involves the idea of having the product made available when needed by the customer. The customer may buy a turkey a few days before Thanksgiving without having to plan to have it available. Intermediaries take care of the logistics to have the turkeys—which are easily perishable and bulky to store in a freezer—available when customers demand them. Possession utility involves the idea that the consumer can go to one store and obtain a large assortment of goods from different manufacturers during one shopping occasion. Supermarkets combine food and other household items from a number of different suppliers in one place. Certain “superstores” such as the European hypermarkets and the Wal-Mart “super centers” combine even more items into one setting.

The marketing vs. the selling concept. Two approaches to marketing exist. The traditional selling concept emphasizes selling existing products. The philosophy here is that if a product is not selling, more aggressive measures must be taken to sell it—e.g., cutting price, advertising more, or hiring more aggressive (and obnoxious) sales-people. When the railroads started to lose business due to the advent of more effective trucks that could deliver goods right to the customer’s door, the railroads cut prices instead of recognizing that the customers ultimately wanted transportation of goods, not necessarily railroad transportation. Smith Corona, a manufacturer of typewriters, was too slow to realize that consumers wanted the ability to process documents and not typewriters per se. The marketing concept, in contrast, focuses on getting consumers what they seek, regardless of whether this entails coming up with entirely new products.

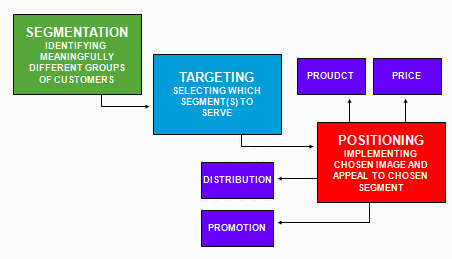

The 4 Ps—product, place (distribution), promotion, and price—represent the variables that are within the control of the firm (at least in the medium to long run). In contrast, the firm is faced with uncertainty from the environment. Segmentation, Targeting, and PositioningSegmentation, targeting, and positioning together comprise a three stage process. We first (1) determine which kinds of customers exist, then (2) select which ones we are best off trying to serve and, finally, (3) implement our segmentation by optimizing our products/services for that segment and communicating that we have made the choice to distinguish ourselves that way.

Segmentation involves finding out what kinds of consumers with different needs exist. In the auto market, for example, some consumers demand speed and performance, while others are much more concerned about roominess and safety. In general, it holds true that “You can’t be all things to all people,” and experience has demonstrated that firms that specialize in meeting the needs of one group of consumers over another tend to be more profitable. Generically, there are three approaches to marketing. In the undifferentiated strategy, all consumers are treated as the same, with firms not making any specific efforts to satisfy particular groups. This may work when the product is a standard one where one competitor really can’t offer much that another one can’t. Usually, this is the case only for commodities. In the concentrated strategy, one firm chooses to focus on one of several segments that exist while leaving other segments to competitors. For example, Southwest Airlines focuses on price sensitive consumers who will forego meals and assigned seating for low prices. In contrast, most airlines follow the differentiated strategy: They offer high priced tickets to those who are inflexible in that they cannot tell in advance when they need to fly and find it impractical to stay over a Saturday. These travelers—usually business travelers—pay high fares but can only fill the planes up partially. The same airlines then sell some of the remaining seats to more price sensitive customers who can buy two weeks in advance and stay over.

Note that segmentation calls for some tough choices. There may be a large number of variables that can be used to differentiate consumers of a given product category; yet, in practice, it becomes impossibly cumbersome to work with more than a few at a time. Thus, we need to determine which variables will be most useful in distinguishing different groups of consumers. We might thus decide, for example, that the variables that are most relevant in separating different kinds of soft drink consumers are (1) preference for taste vs. low calories, (2) preference for Cola vs. non-cola taste, (3) price sensitivity—willingness to pay for brand names; and (4) heavy vs. light consumers. We now put these variables together to arrive at various combinations.

In the next step, we decide to target one or more segments. Our choice should generally depend on several factors. First, how well are existing segments served by other manufacturers? It will be more difficult to appeal to a segment that is already well served than to one whose needs are not currently being served well. Secondly, how large is the segment, and how can we expect it to grow? (Note that a downside to a large, rapidly growing segment is that it tends to attract competition). Thirdly, do we have strengths as a company that will help us appeal particularly to one group of consumers? Firms may already have an established reputation. While McDonald’s has a great reputation for fast, consistent quality, family friendly food, it would be difficult to convince consumers that McDonald’s now offers gourmet food. Thus, McD’s would probably be better off targeting families in search of consistent quality food in nice, clean restaurants. Positioning involves implementing our targeting. For example, Apple Computer has chosen to position itself as a maker of user-friendly computers. Thus, Apple has done a lot through its advertising to promote itself, through its unintimidating icons, as a computer for “non-geeks.” The Visual C software programming language, in contrast, is aimed a “techies.”

Michael Treacy and Fred Wiersema suggested in their 1993 book The Discipline of Market Leaders that most successful firms fall into one of three categories:

Treacy and Wiersema suggest that in addition to excelling on one of the three value dimensions, firms must meet acceptable levels on the other two. Wal-Mart, for example, does maintain some level of customer service. Nordstrom’s and Intel both must meet some standards of cost effectiveness. The emphasis, beyond meeting the minimum required level in the two other dimensions, is on the dimension of strength.

To effectively attempt repositioning, it is important to understand how one’s brand and those of competitors are perceived. One approach to identifying consumer product perceptions is multidimensional scaling. Here, we identify how products are perceived on two or more “dimensions,” allowing us to plot brands against each other. It may then be possible to attempt to “move” one’s brand in a more desirable direction by selectively promoting certain points. There are two main approaches to multi-dimensional scaling. In the a priori approach, market researchers identify dimensions of interest and then ask consumers about their perceptions on each dimension for each brand. This is useful when (1) the market researcher knows which dimensions are of interest and (2) the customer’s perception on each dimension is relatively clear (as opposed to being “made up” on the spot to be able to give the researcher a desired answer). In the similarity rating approach, respondents are not asked about their perceptions of brands on any specific dimensions. Instead, subjects are asked to rate the extent of similarity of different pairs of products (e.g., How similar, on a scale of 1-7, is Snicker’s to Kitkat, and how similar is Toblerone to Three Musketeers?) Using a computer algorithms, the computer then identifies positions of each brand on a map of a given number of dimensions. The computer does not reveal what each dimension means—that must be left to human interpretation based on what the variations in each dimension appears to reveal. This second method is more useful when no specific product dimensions have been identified as being of particular interest or when it is not clear what the variables of difference are for the product category. |